Tug Pilot Information on Engine Icing

The Lycoming O-360 engine that is fitted to all our tug aircraft is liable to engine icing in certain conditions. In extreme circumstances the engine may stop altogether or may just cause rough running. Either way it is important to be alert to the ambient conditions that produce engine icing potential and be methodical in protecting your engine against it’s formation.

Types of Icing

There are three types of icing that can affect our engines.

a. Carburettor Icing

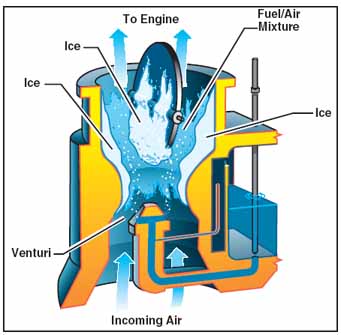

The most common, earliest to show, and the most serious, is carb icing. This is caused by the sudden temperature drop due to fuel vaporisation and pressure reduction at the carburettor venturi. The temperature drop may be as much as 30ºC and results in atmospheric moisture forming ice which gradually blocks the venturi. This slowly strangles the engine upsetting the fuel/air ratio causing a progressive, smooth loss of power. The conventional float type carburettor, as fitted on our engines, being more prone to icing than pressure jet types. The diagram to the left clearly shows this.

b. Fuel Icing

Less common, is fuel icing, which is the result of water, held in suspension in the fuel, precipitating out and freezing in the induction piping.

c. Impact Icing

Ice that builds up on air intakes and filters by operating in snow, sleet, sub-zero cloud and rain is known as Impact Icing. It will obviously adversely affect the performance of both your engine and aircraft.

Conditions conducive to Carburettor Icing

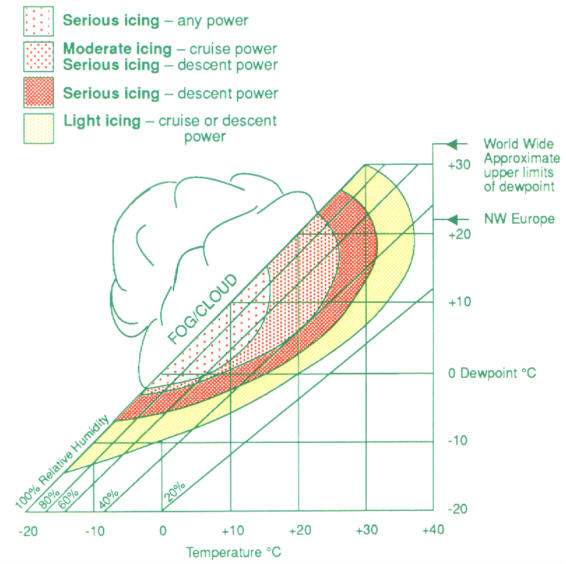

The diagram below shows the Temperature/Dew Point combinations that can lead to carb icing. It is worth noting that even on a summer day with a temperature of 25 ºC given high humidity, carb icing is possible.

Clues to high humidity include the following;

- Operating close to cloud base.

- Operating in precipitation.

- If the ground is wet from dew or recent rain.

- Operating in reduced visibility.

- Operating in clear air where fog or low cloud has just dispersed

Cold days where the visibility is poor, where the cloud base is low or a clear day with heavy dew or frost should be regarded as days when carb icing is most likely.

Recognition of Carb Icing

A slight drop in RPM is the mostly likely indication of the onset of carb icing, although rough running is another.

In cruise or descent this will happen slowly and without any throttle movement.

On take-off, if full power is not achieved. It is obviously important to know the normal maximum RPM for each of our engines in order to detect this. Note:- Leaving the carb heat on would give a similar indication.

Precautions to take as pilots

- Operate carb heat immediately after a cold engine start.

- Operate carb heat prior to take-off.

- Check that max rpm is attained during take-off.

- Operate carb heat in descent, if the flight has gone up to or beyond cloudbase.

- Operate carb heat during or after prolonged ground running.

- Operate carb heat during the approach checks as normal.

Normal Carburettor Heater operation

Normal carb heat operation is to fully select for 10 to 20 seconds and then return to cold.

If the engine returns to the settings before operation then there is no icing, However, if the engine runs more smoothly or the engine rpm returns to a higher value than before, then you have had carb icing and have removed it or part of it. In these circumstances repeat the check until it is obvious the ice has cleared and be vigilant against further build ups. Do not fly with the carb heat on all the time, under certain circumstances ice can still form and then there is no way of getting rid of it. The device is works as a de-icer NOT and anti-icer.

If you have experienced carb icing, advise other tug pilots.

CAA Safety Sense Leaflet – Piston Engine Icing can be seen here.

Loading...

Loading...

Return to ‘Aircraft’ Return to ‘Front Page’