Engine Handling Propeller Considerations Noise Abatement Sunset Weather Conditions Checklists Operations with Winching Passenger Carrying Tug Hire Booking In/Out

Tug Pilot Manual

It is important to remember that as a Tug Pilot you have considerable responsibility to the London Gliding Club. Aero-towing is an expensive and noisy operation. Both factors have a bearing on the very existence of the gliding club and it is essential, therefore, that Aero-towing be carried out efficiently and thoughtfully, particularly with regard to our neighbours.

Aero-towing should be carried out in accordance with the following procedures and in conjunction with the London Gliding Club’s Operations Manual and Club Rules. The TPM has been generated with years of experience of towing and knowledge of the aircraft that we use. The procedures take into account risk mitigation and gives checklists (although in paragraph form) to comply with our Non-Commercial Operations (SPEC) obligations. Whilst they must be followed during standard operations, it is recognised that the pilot-in-command may on occasion need to deviate from these procedures on the grounds of safety. Please inform the CTP if this was to happen.

Within these constraints the glider pilot’s requirements should be accommodated as far as possible.

Engine Handling

One of the most important aspects of our operation is the way we operate our tug engines. The style of operation with lots of take-offs, full power climbs and relatively swift descents followed by often protracted ground time with low power settings puts a lot more demand on an engine in terms of internal stresses and temperature “shocks” than an engine typically found in the general aviation world.

It is imperative that every tug pilot be fastidious in this aspect of tug flying. The following list represents a summary of critical engine points. They are repeated in context in other areas, particularly the Robin Operations section. The engine is air cooled which is generally fine in flight but potentially problematic on the ground however there a several disciplines you should adhere to, and smooth use of the throttle should be high amongst them.

- Start up – Avoid high RPMs as the engines starts. Throttle should be set just forward of idle to achieve 1000 rpm. It should be immediately checked to this value after start up.

- Taxiing – Always keep the RPM below 1500rpm whilst on the ground. Hangar ridge can be climbed with 1500 rpm or less providing correct technique is used. Position in such a way that high power, tight taxiing manoeuvres are not required. Be aware of wind direction and whenever possible do any extended ground running in to wind. With anything beyond a normal turnround, either shut-down or point into wind.

- Run up – Into wind and keep high power to the minimum required for the checks. It is important to do this at the correct time, see notes on engine ground run.

- Take-off – Apply progressively and smoothly to full throttle over 3 seconds, yes 3 seconds.

- Glider Release – Follow the technique defined in Robin Operations. If you find that you’re approaching cloud base, ensure you don’t run into cloud and have to short cut the standard procedure.

- Descent – A normal descent will require gradual power reduction at each phase. The point where you close the throttle to make the landing should be as late as possible during the approach.

- Go-around – Be as gentle as circumstances permit.

- Shut down – Once the tug has stopped and brakes applied, allow the engine to idle at 1000 rpm for a short time to allow it to adequately cool prior to shutting down as per the procedure in Robin Operations.

Propeller Considerations

After the engine, the next most important part of our aircraft is the propeller.

We should take very good care of it. If only one part of the aircraft is clean before flying it should be the propeller. Think of it as a high-speed wing profile with laminar flow across its leading edge, so any chips, dents or bugs are going to reduce its aerodynamic performance and the amount of thrust that it can generate.

Stone damage

It doesn’t take much to chip a propeller, then those blemishes will affect the propeller’s performance until it gets refurbished which could be years away. It is important that we make every effort to avoid the small stones that might damage the propeller.

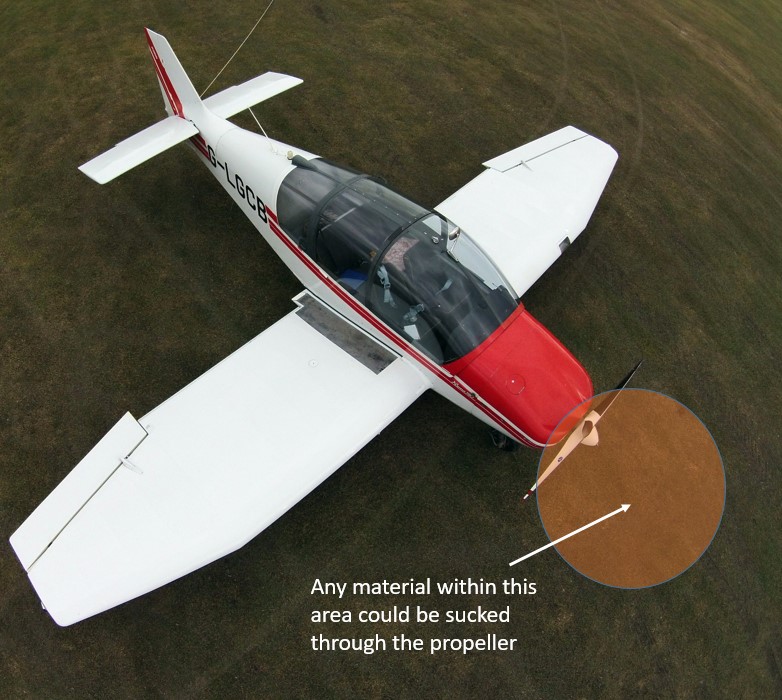

The four blade propeller fitted on our DR400s has an unfortunate characteristic in that, at low power settings and whilst stationery or moving slowly, it creates a vortex ahead and below the propeller which has the capability of sucking small stones and debris through the propeller disc with damaging consequences. The diagram below shows the critical area around the propeller. Two blade propellers are generally less susceptible, however, good practice suggests you taxi and position as you would with a four blade propeller.

It is for this reason we should not run these engines over areas with small exposed stones, this includes the peri-track, apron, area in front of the pumps and those bald areas on the air-side of the peri-track. When parking your aircraft ensure it can be taxied away without going over any stony patches.

Bugs

As for bugs, they can be cleaned off. Make sure the propeller is clean before towing. If it’s a particularly buggy day it might need cleaning during the day.

Rain and hail

Heavy rain and hail, if flown through, has the capability of stripping the paint from the leading edges and could cause considerable damage. It may be stating the obvious, but don’t go flying if it’s raining or you are likely to encounter rain.

Noise Abatement

Continual towing or descent over the same area causes considerable nuisance and irritation to our neighbours. Whilst we can do little to reduce the actual noise produced, we can spread the load by thoughtful and varied tow-patterns. It is variation, therefore, that forms the basis of our noise abatement procedures. The following general points should be considered, along with specific procedures as laid down in the ‘Launch Points’ pages of this website. You can also find a selection of example tow patterns that conform with these principles in Tow Out Patterns.

- Avoid over-flying all houses just after take-off, these are clearly marked on the diagrams associated with the different Launch Points.

- Fly around the group of villages – Edlesborough, Eaton Bray and Totternhoe unless absolutely necessary. Do not tow over Dunstable below 1500′. See diagram below.

- Use the airspace directly over the London Gliding Club (see the ‘Airspace’ page).

- Make full use of all airspace available to us within the Luton SRZ (see the ‘Airspace’ page).

- It is not always necessary to drop upwind, a tow made for most part downwind of the site and then terminating overhead or slightly upwind of the site can sometimes be used.

- Remember that when turning, the focal point of your turn (the lower wing will be pointing at it) will be subjected to a concentration of tug noise.

- A soaring pilot may be happy to be towed directly away from the site, this should be done when the opportunity arises.

- Evenings and Sundays are particularly sensitive periods.

Remember that the noise of a descending tug with a relatively high power setting can be equally annoying, apply the same routing considerations in the descent as well. Additionally, try and make your descent route different from the tow out route. Do not descend below 500′ until entering the base leg.

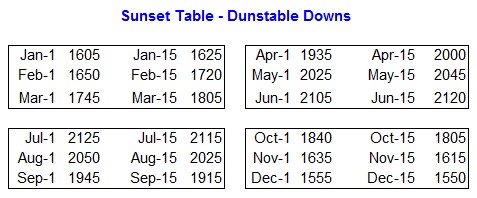

Sunset

It is the tug pilots responsibility after full consultation with the instructor in charge, to terminate aero-tow operations when darkness approaches. Do not launch a glider after sunset +10 minutes. It maybe prudent to stipulate an earlier time if cloud reduces light or visibility. Advise the instructor in charge of this time in advance and don’t succumb to commercial pressures.

Weather Conditions

It is the tug pilots responsibility to terminate aero-tow operations if visibility, wind strength/direction, cloud base or adverse surface conditions make operations hazardous. Remember a lot of conditions you or a tug might fly in, might not be safe or sensible in a glider or for an inexperienced pilot.

If you feel the need to test conditions in a tug, clearly operations are marginal. Your guiding principle must be “If in doubt, DON’T”.

In conditions of strong Southerlies, consider the needs of the glider pilots; towing towards Leighton Buzzard (downwind) is unlikely to be a good idea. Aim to drop the gliders along the southern boundary of our usable airspace – this may be over the club, the southern end of Dunstable or between Edlesborough Church and Ivinghoe Aston.

We should not be flying in visibility under 5km. This is equivalent from the clubhouse to Ivinghoe Beacon.

Do not fly when it is raining, not only is visibility and performance affected, but damage can also be caused to the propeller. Tugs should not be refuelled when it is raining.

As a general rule do not aero-tow on a snow covered field. Under some circumstances it may be possible to establish an operation on a snow covered field but there are too many variables to list here, so consult with the CTP or DCTP if a need arises.

If a tug pilot has declined to tow because of the weather conditions, it would be inappropriate for another pilot to then tow instead.

Checklists

There are no printed checklists issued. However, that does not mean no checks, instead for every phase of flight where a checklist might be consulted in a GA aircraft, the tug pilot will run a pertinent check by way of a scan. The scan should follow a consistent route around the cockpit starting in the centre with the flap lever, running forward, then left to right across the base of the panel, then left right across the top of the panel, then rising to the canopy and catch (or locating pins and clamp in the case of YM) and finally ending with the pilot’s straps. This will work for start up, power check and before take-off. In flight, scans should be short and pertinent to minimise “head in cockpit” time. Before landing check should include trim, carb heat and brakes off as a minimum and should be completed at the 500′ level off or just before. Shutdown checks should be done when stationary and will allow a short “cool down” at 1000 rpm. Electrical items should be turned off, carb heat checked before shutting the engine down followed by switches and master off, flaps down.

With reference to the ‘Emergencies’ section, each pilot should have a clear idea in their mind of the actions in the event of an emergency on every flight.

Initial training will provide new tug pilots with this essential discipline. Guidance from the CTP or DCTP is always available.

Operations when winching is taking place

Before take-off, check that a winch launch is not taking place or about to take place. If it is, delay launching until the cable is back on the ground. Do not take-off across cables. If there is a cable tractor drawing out cables, again, delay launching until it is stationery and/or safely out of the way of the take-off run in order to minimise the consequences of an abandoned aero-tow launch.

It is acceptable, on the SW run only, to be on approach or landing with a simultaneous winch launch taking place. The tug pilot should be alert to a potential cable break during the winch launch and if appropriate make a go-around to facilitate the glider pilot’s emergency landing.

Passenger Carrying

Passenger carrying is NOT allowed whilst aero-towing. Exceptions to this rule must have specific authorisation from the CTP or DCTP.

Tug Hire

Tug aircraft may on occasions be available to hire. However, approval will always be required from the CTP, DCTP or CFI. The pilot will be charged according to the charges shown in the LGC price list.

Booking In/Out

It is a legal requirement that all powered aircraft movements not starting and finishing their flights at Dunstable (i.e. most flights other than normal aero-tows) should be recorded. A movement book is located outside the main office, it has two sections, the first for visitors taking details of departure point and destination and a second section for LGC tugs recording either a destination or a departure point.

All aero-tow retrieves, positioning flights or hire flights should be entered.

Return to ‘Operations’ Return to ‘Front Page’