From time to time over the years, tug upsets have occurred at low level from which the tug has been unable to recover, often with fatal consequences. A glider pilot’s aero-tow training emphasises that correct position behind the tug is essential and that they must release if they are losing control.

However, tug pilots must be vigilant during the early stages of the launch for any tendency of the tug to be pitched nose down. Below 800 feet, monitor the tugs attitude and if a gentle back pressure is insufficient to prevent any nose down pitch – release immediately. Resist the temptation to look in the mirror and act on the changing attitude. Above 800 feet, the glider pilot may be given the opportunity of correcting the situation. Be aware that tug upsets can happen rapidly with little warning.

The tug pilot should identify the release before each flight, essential when changing aircraft where the release handle may be different and/or in a different place.

There are a number of factors which increase the possibility of a tug upset:

Regarding the Glider/Glider Pilot;

- A glider that is to be towed from the belly hook.

- Gliders with high set wings to the towing hook.

- Gliders with a low wing loading, usually older or vintage types.

- Glider pilots with low hours and/or aero-tow experience.

- Glider Pilots doing early stage aero-tow training, the instructor should control this but they don’t always – beware.

- Lightweight pilots

- The use of short tow ropes will also exacerbate the problem.

Regarding the Tug/Tug Pilot;

- Incorrect trim setting.

- Forgetting to use take-off flaps.

- Retracting flap too soon after take-off.

- Low experience as a tug pilot.

- Not being completely fit to fly giving rise to a low level of alertness.

- Towards the end of a long towing session, where tiredness or complacency will reduce your ability to react appropriately.

- The Super Cub is less tolerant than a Robin.

- Zooming after take-off.

Regarding other factors;

- Marginal flying conditions. A strong wind gradient, gusty winds, wind off the hill, turbulence and crosswinds. All of these conditions will potentially mask the early signs of a tug upset.

- Rough surface, which may launch a glider (or a tug for that matter) prematurely into the air.

- Distractions caused by other flying activities around you.

Some of these factors you can control directly, others you can deal with providing you are alert.

If, with all things considered you are not comfortable to make a tow, then don’t. Or share your concerns with the duty instructor.

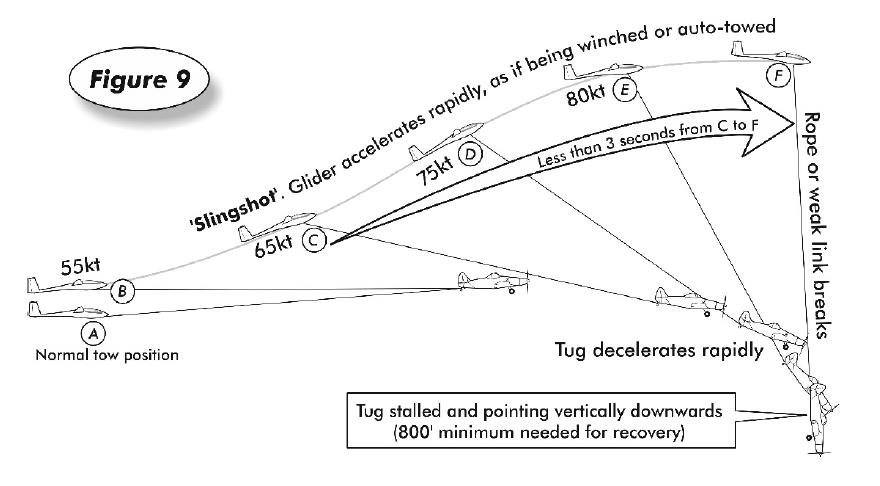

A typical sequence is shown above (extract from the BGA instructor manual), with a simplified rope load/angle plot below. In reality the situation is worse than shown because the glider zoom climbs behind the tug and it’s total energy increases (simultaneous increase in height and speed). This energy can only come from the momentum of the tug and therefore it’s speed will rapidly decay. This means that just when a high down load is required to be generated by the tailplane/elevator to retain control and break the weak link of the rope, it’s capability to do is is vastly reduced by the decay in airspeed. This may result in the tailplane, and possibly the wing, stalling. Typically, up to 800 feet may be required to recover from an upset.

Also, avoid a hasty transition from level acceleration to climb, as this will result in the glider becoming low relative to the tug. This can tempt the glider pilot to make a rapid recovery, with obvious possibility for over correction.

In addition, there are other destabilising influences for both tug and glider pilot, such as re-trimming, flap and undercarriage retraction, instrument scan, looking in the rear view mirror, etc. For the tug pilot, retracting flaps should be left to a safe height, at least 300 feet.

Since upsets are, fortunately, rare events and tug pilots may not have experienced any before, the overriding advice is; any unusual behavior of the tug or glider in the early stages of the launch is cause for immediate release of the tow rope. The analysis can be done afterwards.

From the Glider

Glider pilots knowledge of tug upsets and how they should be avoided comes from training and refresher documents that are circulated from time to time – such as the ‘BGA Safe Aerotowing Booklet’. Should any tug pilot have any concerns around a glider pilot’s aero-towing skills then this should be brought to the attention of the CFI and CTP or their deputies at the earliest opportunity.

Loading...

Loading...

Return to ‘Emergencies’ Return to ‘Operations’ Return to ‘Front Page’